Why did I build a band organ? Well, the simple answer would be that I

had a desire to own one and buying one can be an expensive proposition.

But more important for me was the idea of creating a band organ from

basic materials and the sense of accomplishment that would bring. I had

restored a number of player pianos and a player reed organ but this

project would be different in that I would be starting from "scratch".

Actually I had something smaller in mind. For several years I had

considered building a street organ or monkey organ but could not find

suitable plans. Then about three years ago I learned that plans were

available for a replica of a Wurlitzer 105 band organ. I obtained a set

of the plans and after studying them for a few days I said, "I can do

that." There were a couple of items such as the crankshaft and roll

frame that were probably beyond my metalworking abilities but it was my

understanding that there were some individuals out there that could

provide those items!

Why did I build a band organ? Well, the simple answer would be that I

had a desire to own one and buying one can be an expensive proposition.

But more important for me was the idea of creating a band organ from

basic materials and the sense of accomplishment that would bring. I had

restored a number of player pianos and a player reed organ but this

project would be different in that I would be starting from "scratch".

Actually I had something smaller in mind. For several years I had

considered building a street organ or monkey organ but could not find

suitable plans. Then about three years ago I learned that plans were

available for a replica of a Wurlitzer 105 band organ. I obtained a set

of the plans and after studying them for a few days I said, "I can do

that." There were a couple of items such as the crankshaft and roll

frame that were probably beyond my metalworking abilities but it was my

understanding that there were some individuals out there that could

provide those items!

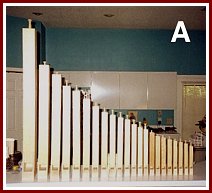

Starting the project it seemed to me that the most critical items would

be the pipes. It would be extremely frustrating to build the case,

bellows, etc. first and then find out that one could not build a pipe

that worked. So based on that I decided to build a few smaller pipes

just to see if I could. I started with one of the smaller stopped flutes

from the melody section. In PHOTO A these would be the small pipes at

the right. The large pipe to the left is approximately four feet long

which will give you some idea of the size of the other pipes. After

assembling the pipe I tested it by blowing with my mouth, not really the

way to test pipes but I will have more to say about that later. To my

amazement it actually made a sound, and a pleasant sound at that. This

was encouraging. I put together five more pipes in that section. I was

able to tune them to the proper pitch using an electronic guitar tuner as

a guide. However, the only source of wind I had was my own breath and

that is not a controllable or constant pressure. Organ pipes are voiced

and tuned to operate at a specific air pressure. If the pressure is

increased the pitch will also rise. If the pressure is decreased the

pitch of the note will drop. If I were to continue it would be necessary

to have some sort of test box to provide a constant source of air

pressure and a valve for turning it on and off. I should mention at this

point that after successfully constructing a few small pipes I decided to

try something larger and ended up building the largest pipe in the organ,

the four foot bass G pipe at the left in the picture above.

Starting the project it seemed to me that the most critical items would

be the pipes. It would be extremely frustrating to build the case,

bellows, etc. first and then find out that one could not build a pipe

that worked. So based on that I decided to build a few smaller pipes

just to see if I could. I started with one of the smaller stopped flutes

from the melody section. In PHOTO A these would be the small pipes at

the right. The large pipe to the left is approximately four feet long

which will give you some idea of the size of the other pipes. After

assembling the pipe I tested it by blowing with my mouth, not really the

way to test pipes but I will have more to say about that later. To my

amazement it actually made a sound, and a pleasant sound at that. This

was encouraging. I put together five more pipes in that section. I was

able to tune them to the proper pitch using an electronic guitar tuner as

a guide. However, the only source of wind I had was my own breath and

that is not a controllable or constant pressure. Organ pipes are voiced

and tuned to operate at a specific air pressure. If the pressure is

increased the pitch will also rise. If the pressure is decreased the

pitch of the note will drop. If I were to continue it would be necessary

to have some sort of test box to provide a constant source of air

pressure and a valve for turning it on and off. I should mention at this

point that after successfully constructing a few small pipes I decided to

try something larger and ended up building the largest pipe in the organ,

the four foot bass G pipe at the left in the picture above.

I considered building a test box for voicing and tuning each pipe as I

constructed them, but opted instead to go ahead with the wind chest. The

pipe feet sit in the wind chest and inside the chest there is a valve for

each note, therefore it could be used for testing without having to build

a separate test fixture. For an air supply I purchased a blower box from

the Player Piano Company in Wichita, Kansas. The blower box has a motor

speed control so that it can be adjusted to provide the correct amount of

pressure, in this case 8 inches of water. In pounds per square inch this

would be less than one psi. An organ does not require a very high

pressure but does need a fair volume of air.

I considered building a test box for voicing and tuning each pipe as I

constructed them, but opted instead to go ahead with the wind chest. The

pipe feet sit in the wind chest and inside the chest there is a valve for

each note, therefore it could be used for testing without having to build

a separate test fixture. For an air supply I purchased a blower box from

the Player Piano Company in Wichita, Kansas. The blower box has a motor

speed control so that it can be adjusted to provide the correct amount of

pressure, in this case 8 inches of water. In pounds per square inch this

would be less than one psi. An organ does not require a very high

pressure but does need a fair volume of air.

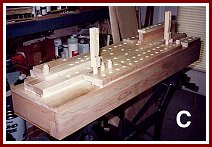

Parts of the organ that need to be airtight, such as the wind chest, are

usually made of a dense, low porosity wood. Maple is an excellent choice

for this application. In addition it is a strong wood not prone to

splitting. PHOTO B shows the beginnings of the chest. If you look

closely you can see holes drilled in the top of the chest for the various

pipes. In reality the pipe feet do not fit directly into these holes.

In PHOTO C one can see that the tapered pipe feet actually fit into

tapered holes in a board which sits above the openings in the chest.

Sandwiched in between is a slider with matching holes. This slider can

be moved lengthwise so the holes do not line up and thus cut off the air

to that set of pipes. PHOTO D shows the underside of the wind chest at

this point in its construction. It is divided into channels, one for

each of the 41 notes.

Parts of the organ that need to be airtight, such as the wind chest, are

usually made of a dense, low porosity wood. Maple is an excellent choice

for this application. In addition it is a strong wood not prone to

splitting. PHOTO B shows the beginnings of the chest. If you look

closely you can see holes drilled in the top of the chest for the various

pipes. In reality the pipe feet do not fit directly into these holes.

In PHOTO C one can see that the tapered pipe feet actually fit into

tapered holes in a board which sits above the openings in the chest.

Sandwiched in between is a slider with matching holes. This slider can

be moved lengthwise so the holes do not line up and thus cut off the air

to that set of pipes. PHOTO D shows the underside of the wind chest at

this point in its construction. It is divided into channels, one for

each of the 41 notes.

These channels line up with the openings for the pipes in the top of the chest. At the far side can be seen openings

through which air flows from a channel, through a connecting duct down to

one of the pipes which are mounted in the lower part of the organ. The

wooden strip across the channels provides a place to attach the hinges of

the pallet valves, one for each channel. PHOTO E shows the pallet valves

with their leather hinges glued into place. The remaining open area of

the channels is covered with an airtight cloth normally used to cover

small bellows. This can be seen as the red area behind the pallet

valves. In the next section I will go into a little more detail about

the pallet valves.

These channels line up with the openings for the pipes in the top of the chest. At the far side can be seen openings

through which air flows from a channel, through a connecting duct down to

one of the pipes which are mounted in the lower part of the organ. The

wooden strip across the channels provides a place to attach the hinges of

the pallet valves, one for each channel. PHOTO E shows the pallet valves

with their leather hinges glued into place. The remaining open area of

the channels is covered with an airtight cloth normally used to cover

small bellows. This can be seen as the red area behind the pallet

valves. In the next section I will go into a little more detail about

the pallet valves.

Editors note: Howard is a retired electrical engineer. Most of his

career was at the Army Night Vision and Electro-Optics Laboratory. He

became involved in mechanical music with the purchase of a non-working

player piano. As you will see in his articles, Howard is a highly skilled

craftsman. Building your own band organ is a real accomplishment and

Howard does beautiful work. Howard can be contacted at:

hwyman@tampabay.rr.com